The Mississippi River is a beast! Stretching an incredible 2,350 miles, it navigates through 10 states and 29 “Mississippi River flood control systems” to discharge some 593,000 cubic feet of water per second into the Gulf of Mexico. No big deal right?

Wrong. Not only is the Mississippi River the fourth largest river in the world — just behind the Amazon, Nile, and Yangtze Rivers — but it drains an area of 1.2 million square miles, or roughly 40% of the continental United States.

Despite its commanding presence however, the Mississippi River is in trouble. And as it reaches its final stop in Louisiana, the meandering river has just one option to avert flooding in case of emergency — the Bonnet Carre Spillway.

And this is where it all goes wrong.

Why Is The River Leveed? A Quick History Lesson

To provide a quick recap, the Mississippi River is walled off by large, earthen structures called “levees.” The primary intent of these structures? To prevent flooding and contain the river.

But before it was leveed, the river would naturally do two things: (1) it would deposit nutrients throughout the floodplain when it swelled, and (2) it would deposit sediment to build land, especially along its banks.

The Great Flood of 1927 permanently changed that.

In what is now known as one of the worst flooding disasters in United States history, the Great Flood of 1927 was the final nail in the coffin for the once free-flowing river. After flooding 23,000 square miles and killing over 250 people, lawmakers had had enough. They wanted a more “permanent” solution.

The following year, the government enacted the 1928 Flood Control Act, which essentially mandated that the grade of the levees be improved and that different flood scenarios be considered. Additionally, the idea of spillways — big controllable breaks in the river that could release water during high flow times — became the ultimate “in case of emergency” button.

The Problem With Mississippi River Flood Control

The initial problem today is two-fold (and as always, both man made). On one hand, there’s the predictable problem — that the levees are unnatural; they force the river in a single direction instead of letting it naturally wonder. As the river is unable to drop sediment off on its banks, it makes deposits along its riverbed, forcing us to build the levees higher as the ground builds up and the river rises.

On the other hand, there’s the less obvious problem — the effects of development and climate change.

While the Mississippi River has always flooded in the Spring (yes, there are in fact flood seasons), the flooding has exponentially increased in the last decade. This is due to two reasons – (1) there is increased rainfall in the Midwestern part of the United States causing the amount of water flowing along the Mississippi to increase, and (2) man made changes such as agricultural practices, urban development, forest cover, and general flood management activities have prevented groundwater recharge and “rushed” water straight to the river (or a tributary, close body of water, etc.).

To better understand this phenomenon, picture a town next to the Mississippi River (or one of its tributaries) and think about the level of expansion (or growth) that’s happened to it over the last few decades. Now think about what that entails from an environmental standpoint.

Trees that soak up water get removed, homes replace vegetation, rooftops displace rainfall; eventually, concrete stops it all, preventing water from ever hitting the ground. As the ground isn’t able to do its job and soak up anything, it causes more water to flow into the river, swelling the river in the process.

. . eventually, concrete stops it all, preventing water from ever hitting the ground

So, the big overarching problem is that the river is swelling and getting dangerously close to topping the levees every year.

The more immediate problem however, is what happens when we try to prevent the river from overtopping the levees using “Mississippi River flood control systems.”

Enter the Bonnet Carré Spillway.

The Bonnet Carré Spillway

If there is ever raw, physical proof that climate change is happening, it’s the Bonnet Carré Spillway.

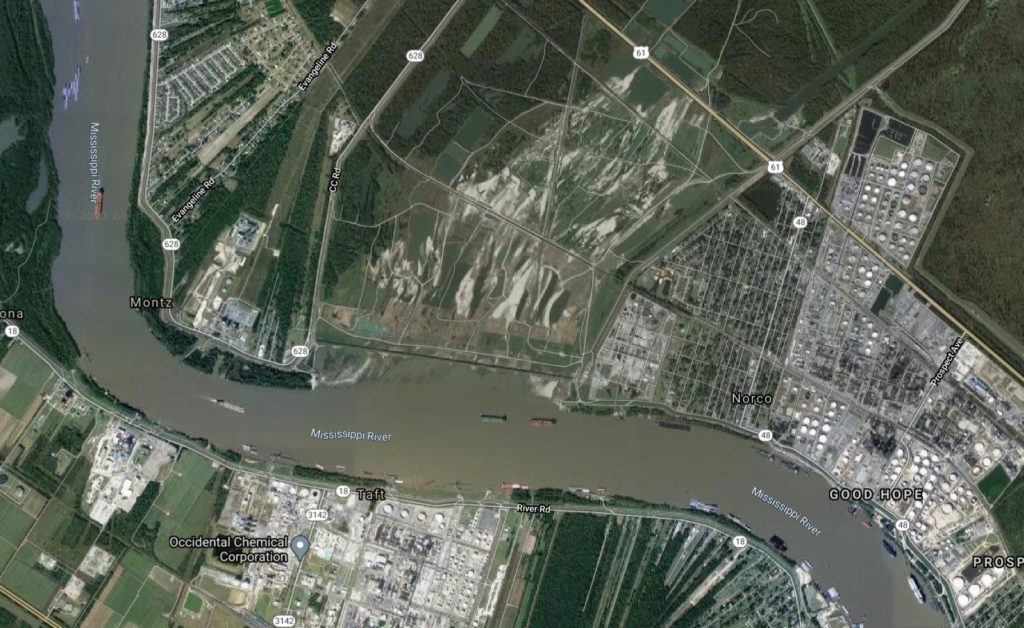

Constructed between 1929 and 1931, the Bonne Carre Spillway sits about 32 miles upriver from New Orleans and serves as an emergency spillway for the City. When the River gets too high — threating to flood New Orleans — the floodgates are opened, the river levels go down, and New Orleans is saved.

Thank God, because the world needs crawfish, mardi gras, daquirees, and Drew Brees. In that order.

Having only been opened 15 times since 1931, seven of those openings have occurred within the last 13 years — those include openings in 2008, 2011, 2016, 2018, twice in 2019, and 2020.

Having only been opened 15 times since 1931, seven of those openings have occurred within the last 13 years

And while this is great news for New Orleans, it’s not so great news for the natural environment around New Orleans.

That’s because every time the spillway is opened, millions of gallons of freshwater pour into Lake Pontchartrain (which is strangely not actually a lake), decreasing the salinity of the water and bringing a host of environmental problems along with it.

More specifically, as the freshwater moves into the “lake” from the Mississippi River, the water infiltrates a high salinity area, completely shocking the estuarine ecosystem and killing marine life in the process. And although Lake Pontchartrain has proven that it can handle and recover from a small opening every decade or so, that’s not what’s happening today.

As the Bonne Carre Spillway is now being opened every single year, the environment simply doesn’t have enough time to recover.

How it affects the Mississippi Gulf Coast

2019 was the first time the Bonnet Carré Spillway was opened twice in one season — it was opened for 123 days and sent 1.35 trillion cubic feet of water water into Lake Pontchartrain.

It didn’t stay in Lake Pontchartrain for long.

Eventually finding its way into the neighboring Mississippi Sound, environmental catastrophes started piling up on top of each other.

As marine life started dying (to include 154 dead dolphins and 175 dead sea turtles) so too did oyster reefs, crabs, and shrimp — a critical lifeline along the Mississippi Gulf Coast. Oyster farmers lost everything while crabbers and shrimpers had to travel to other locations or move farther out to sea with little to no reward for their efforts.

As Alix Rosier wrote in his article A Flood of Catastrophe: How a warming climate and the Bonnet Carré Spillway threaten the survival of Coast fishermen, one fisherman is estimated to have lost 80% of his earnings.

“Usually his 25-cent croakers are the cheapest around, Liebig said. But when supply plummeted and he had to find croakers elsewhere — a four-hour boat ride each way — his monthly fuel spending increased by $1,000 and he was forced to double his prices. For that May, the beginning of shrimp season, he estimates that his year-over-year earnings sank by 80 percent.”

To make matter worse, a pretty significant algae bloom appeared (due to the river’s pollution), shutting down every beach along the coast and releasing a horrible, putrid smell across the region.

With the beaches shut down and swimming restricted, visitors flocked elsewhere.

Mississippi wasn’t happy.

Filing a suit against the the Mississippi River Commission and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers over the 2019 openings, they felt that they were not included in “opening discussions” even though they were the ones most affected.

Mississippi Secretary of State Delbert Hosemann called on the Corps to review their operating procedures, to further study the environmental impacts of freshwater intrusion from the Bonnet Carré Spillway, and to include Mississippi officials when operational decisions are made.

Mississippi River Flood Control Solutions?

So what solutions are on the table? As of this writing, there are really only three:

- Dredge the Mississippi River and make it deeper while building up the levee

- Open the Morganza Spillway before opening the Bonnet Carre Spillway

- Use the Old River Control Structure to slowly allow the river to shift course

1. Corps of Engineers to begin dredging the River: Will make low spots along the levee higher while maintaining the Mississippi River Flood Control Systems

The Corps of Engineers has already started on their solution.

In response to very warranted complaints from Mississippi public officials and local anglers over the opening of the Bonnet Carre Spillway, the Corps of Engineers intends to spend $250 million to dredge the Mississippi River to 50 feet from Baton Rouge to the mouth of the Mississippi River.

While the primary intent of this is to allow ‘Panamax’ ships to travel as far north as Baton Rouge, a large chunk of that $250 million being allocated to address the “Bonnett Carre Spillway situation” and other Mississippi River flood control issues.

In that regard, $8 million is being allocated for a comprehensive study of how to address, manage, and control the flow of water along the lower Mississippi, $12.1 million is being allocated for maintenance and operation of the Old River Control Structure, $5 million is for a Sustainable Rivers Partnership program between the Corps of Engineers, Nature Conservancy, and the state Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority to reassess and study water flow of the Atchafalaya River, and $30 million is allocated for additional Atchafalaya floodway projects.

There has also been a continuing effort by the Corps of Engineers to build up low spots along the levee.

Proposing over $2 billion in upgrades to the Mississippi River levee system, the Corps also intends to shore up protection from Missouri to the mouth of the river, primarily focusing on upgrades for Louisiana.

According to this Times-Picayune/The New Orleans Advocate report, the work will be divided into 143 individual projects across seven states, with 92 projects (or $1.6 billion) going to Louisiana.

The plan calls for construction to begin in 2023 and end in 2026, where they hope to build new and existing levees to a height between 12.5 and 14 feet.

Ironically, one of the low spots happens to be the Corps of Engineer’s New Orleans District office, which can protect water heights between 19 and 19.7 feet. And while Congress authorized construction of new floodwalls at the site to 24 feet in 2014, construction has only just started.

2. To relieve the Mississippi River, flood control along the “Morganza Spillway” is also an option

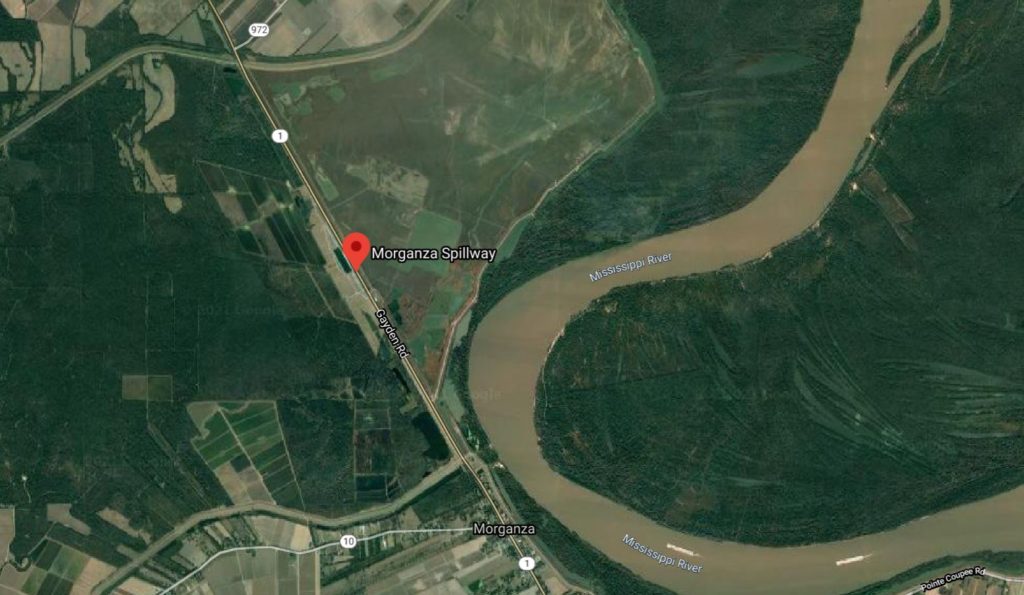

The second solution is simply opening the Morganza Spillway instead of opening the Bonnet Carré Spillway.

Similar to the Bonnet Carré Spillway, the Morganza Spillway is capable of releasing water and relieving pressure on the levees; however, because it sits upriver from Baton Rouge (186 river miles from New Orleans), it would dump water into the Atchafalaya Basin instead of Lake Pontchartrain.

Mississippi obviously favors this solution as it would keep the problem in Louisiana.

As indicated in their lawsuit, “the State has asked the Court to compel the Defendants to perform a Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement as well as to utilize the Morganza Spillway to mitigate the freshwater inundation of the Mississippi Sound in the future.”

But Louisiana has a lot to lose if they open the Morganza Spillway.

According to one report by LSU, the state Department of Natural Resources, and the Louisiana Geological Survey, when the spillway opened in 2011 (only the second opening since 1954), economic losses were estimated at $64 million (in 2019 dollars).

The report indicates that 95,000 acres of crops and 370 acres of aquaculture land were flooded, 5,000 cattle were evacuated, hundreds of Louisiana black bears were displaced or killed, 1,600 whitetail deer were killed, and hundreds of thousands of fish were killed.

People were also affected as hundreds of camps and structures were flooded, commercial navigation was impeded, and about 165 oil or gas wells were shut-in.

Estimated losses are $612,000 for gas and $2.4 million for oil.

3. For the Old River Control Structure, failure is a possibility. Some suggest it’s time to let the Mississippi River flow down the Atchafalaya River before it fails.

Approximately once every thousand years, the Mississippi River bulldozes out of its own banks and carves out a new path, attempting to find the shortest route possible to the Gulf of Mexico.

And while its current course runs through New Orleans and has been around since 1000 A.D., it started to shift towards the Atchafalaya River in the early 1800’s — a course that it used to take some 30000 years ago.

This diversion was accelerated in 1830 when Henry Miller, a steamboat captain, dredged a new channel on the river which shifted the main channel 6 miles to the east. Thus creating the “Old River.”

Approximately once every thousand years, the Mississippi River bulldozes out of its own banks and carves out a new path, attempting to find the shortest route possible to the Gulf of Mexico

By 1950, the Atchafalaya was capturing 20% of the river’s flow and the Army Corps of Engineers grew concerned that a permanent “course change” was imminent. If this happened, they concluded, the river’s shift would bypass both Baton Rouge and New Orleans, leaving them without freshwater, river access, and an economy.

With the help of Albert Einstein’s son — Hans Albert Einstein — the Old River Control Structure was built to act as a controllable bulwark against the Mississippi River’s natural inclination to carve out a new channel to the Gulf of Mexico. Completed in 1963, the structure resembled a dam except that it was controllable. It had gates that could be raised and lowered, limiting the amount of flow leaving the river.

However, as the river’s floods are increasing and the channel has become plugged with sediment, the Old River Control Structure is at risk of failing.

The Solution for the Old River Control Structure?

As Dr. Jeff Masters (co-founder of Weather Underground) writes in his series America’s Achilles’ Heel: the Mississippi River’s Old River Control Structure, one possible solution is to recognize the Old River Control Structure’s limitations and allow the Mississippi River to flow down the Atchafalaya in a controlled fashion.

According to him, failure is inevitable and failure to prepare is asking for a catastrophe with unprecedented global impacts.

He writes that if the structure failed, (1) the Mississippi River would have to close, costing $295 million per day, (2) more than half of U.S. grain exports would start global food shortages for food-insecure countries, (3) flooding would destroy everything along the Atchafalaya including rail lines, pipelines, bridges, and Morgan City, and (4) some 1.5 million people in New Orleans and Baton Rouge would lose their access to freshwater for a multi-month period.

“The Mississippi River will change its channel, and we should make thoughtful plans on how to respond, whether the event happens next year or 100 years from now.”

Dr. Jeff Masters

Other experts have argued similar sentiments, saying that it is better to work with nature rather than against it — that trying to control the Mississippi River was a mistake in its infancy, and it’s still a mistake today.

Instead, by allowing the river to slowly change course down the Atchafalaya, people and infrastructure will have enough time to move. A “managed retreat” so to speak.

Is this a reality? . . . Maybe, but probably not.

Why? Because there’s a whole lot of hurdles to overcome in this solution. Would this help save Lake Pontchartrain and Mississippi? Yes. Would it relieve pressure on the levees and the flood control systems? Yes. But would everyone be for it? No.

Getting this approved would be astronomically difficult. Changing the course of the river would require New Orleans to sacrifice almost everything.

Not only would the city have to find a new drinking source, but they would have to accept the loss of their port (and status), and have to deal with the unintended environmental and socioeconomic changes that would occur as a result (and there would be a lot of them).

But hey, never say never.

In Conclusion, There Really Isn’t A Simple Answer For The “Mississippi River Flood Control” Situation

So there you have it. The problems are endless and the solutions are limited.

Simply put, there is no easy answer and the more you read into it, the more complex it becomes.

And while the Corps has already started on their solution — more dredging and higher levees — who knows how effective that’ll be in the long run. Because if we look at this sort of response historically, we already know how it ends — each time we try to manipulate the river, unintended consequences start stacking up.

So can a natural solution really work?

The short answer is yes — letting the Mississippi River flow down the Atchafalaya would restore the river back to its original form and allow the Mississippi to change course.

But unfortunately, this is a hard sell. As explained above, there’s a human element to all of this which has to be considered. And that’s not necessarily a bad thing.

So what’s the good news?

The good news is that the problem is finally out there in the open. It’s being discussed by local and state leaders, the public knows about it (at least the one’s affected by it do), and its finally getting at least some attention. And with millions in new funding allocated towards the issue, there’s many reasons to be optimistic.

So, bottom line, remain hopeful, but don’t be surprised if the spillway keeps opening. With few options at our disposal, it’s more likely than not.